Gunther Grewe

Games for Criminal Status

Justice as Order

through

Structured Social Inequality

– edited 2022 –

PETER LANG

Frankfurt am Main • Bern • Las Vegas

1979

(European University Papers: Series 2, Law; Bd. 210)

ISBN 3-8204-6480-8

Abstract

The study proposes that we live in a world of social inequality where social status determines our behavior in the observer’s perception.

Depending on the relative social position of the actor and the observer, „saintly behavior“ of the high-status actor may be phenomenologically identical to „deviant behavior“ of the social miscreant but carries rewards for the „saint“ and sanctions for the „deviant.“

Such a view of social texture is sobering. Is Justice „Order through Structured Social Inequality“? The study develops a model of the processes leading to the differential distribution of immunity in society. These processes are a sequence of status degradation ceremonies. In a social psychological model based on game-theoretical conceptualizations, the status degradation ceremonies play a series of games where the grand prize is criminal status.

The study illustrates that the processes leading to criminal status parallel everyday life if we understand social life as a sequence of encounters, as games for social status. Given this understanding, the study of criminology attains a new meaning. It is no longer the study of some marginal, exotic, and esoteric group, be it criminals or criminologists, but as a part of social science, the study of social differentiation in general. Whatever we learn about the dynamics of obtaining criminal status clarifies the criminalization process and holds the properties for a novel understanding of the processes of reality construction in everyday life – of becoming prominent, an outsider, or simply of being a plain man.

For criminological research, the model of games for criminal status conceptualizes the labeling approach and the principle of marginality (i.e., the phenomenon of ubiquity, scarcity, and relativity of marginal positions in social groupings). Based on this model, we can reach a new understanding of justice and, especially, of criminal justice, which would allow us to develop the labeling approach into a theory from which we derive hypotheses whose validity is open to empirical investigation and validation.

The author, a sociologist, uses symbolic interactionist modeling and simulations from game theory. His publications deal with the interdependence of behavior and status. In essence, he observes that marginal positions are ubiquitous, rare, and relative in any social structure. A chilling aspect of the model is that removing someone from a marginal position pushes someone else into the margins of society. Even more chilling is that these processes could be socially engineered and misused.

He previously published „Straßenverkehrsdelinquenz und Marginalität“ (Lang: 1978), a study on the possibilities and limitations of regulating social behavior through law and law enforcement

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCING THE CONCEPT

AND THE MODEL

1.1. Perspective and

Assumptions

1.2. The Concept of

Marginality

1.3. The Model of “Games

for Status”

2. BEYOND THE „COMMON SENSE“: TOWARDS A SCIENCE OF SOCIAL

DIFFERENTIATION

2.1. Criminology as

Caretaker of Rationalizations

2.1.1.

The Controversy on Definitions of „Crime“ and „Criminal“

2.2. Value Neutrality in

Social Science

2.2.1.

Gouldner’s Complaint and the „1′ Art pour 1′ Art“ Approach to Social

Science

2.2.2.

The Problem of Common Sense: Social Science as a Social Activity

2.2.2.1. The Gross Cycle of Social Science

2.2.2.2. The Petite Cycles of Social Science

2.2.2.3.

Value Neutrality as an Attempt to Avoid Ought-Worlds

2. 3. Towards a

Scientific Activity of Criminology

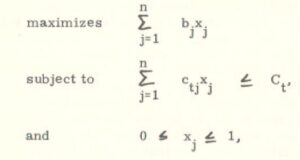

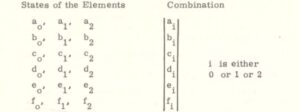

3. BUILDING THE MODEL: NON-MONETARY

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS AS A BASIC BEHAVIORAL PATTERN

3. 1. Decision Theory as

Complementing Behavioral Theory

3.1.1.

The Social Exchange Concept

3.1.2.

The Game-Theoretical Bargaining Model for Social Status

3.2.3.

Status Maintenance and Status Change

3.3. Behavior as

Negotiated Reality

4. APPLYING THE MODEL: THE CRIMINAL

JUSTICE SYSTEM AS AN INSTITUTIONALIZED STATUS SLIDE

4.2. Games for Criminal

Status

4.2.1.

Distributing Negative Esteem

4.2.2.

Choosing Conflict Points

4. 3. Criminal Status

and Criminal Behavior

4.4. Propositions on the

Construction of the Social Reality of Criminal Behavior and Criminal Status

5. SUMMING UP: JUSTICE AS ORDER

THROUGH STRUCTURED SOCIAL INEQUALITY

1. INTRODUCING THE CONCEPT AND THE MODEL

1.1. Perspective and

Assumptions

Criminology has been a layman’s science,

traditionally incapable of transcending insights beyond common sense and

traditionally occupied with rationalizing societal irrationalities. It is the

caretaker of the common-sense notion that life chances depend on social

conduct, i. e., the notion that the good things in life are for the ones who

are well behaved and that the bad things in life are for the ones who violate

social conduct norms. Future historians and sociologists of knowledge might see

traditional criminological theory in the same way as the functional theory of stratification

is presently seen, namely as an attempt to justify and maintain structured

social inequality existing in advanced industrial society.

Common to many criminologists, regardless of whether

they aim at adjusting „the criminal“ to the prevailing social system,

or whether they strive in addition to adjusting the social system to their

ideas of appropriateness, seems to be the belief in the American Dream which

asserts that „all men are born free and equal“ and that

„everyone . . . has the right and often the duty, to try to succeed and to

do his best to reach the top“ (Warner et al., 1949: 3). Common to these

criminologists is a vague idea of justice according to which wrongdoers are or

should be punished only based on their conduct and are or should be assigned

criminal status regardless of their previous social status. Common to these

criminologists, therefore, is their refusal to see the contradictory character

of the American Dream, which disturbs its pastoral idyll of social equality.

They refuse to see that the two fundamental themes of the American Dream,

that all of us are equal and that each one of us

has the right to the chance of reaching the top, are mutually contradictory,

for if all men are equal, there can be no top-level to aim for, no bottom one

to get away from; there can be no superior or inferior positions, but only one

common level into which all Americans are born and in which all of them will

spend their lives (Warner et al., 1949: 3).

They refuse to recognize the possibility that a

common sense ought-world might exist, structuring the is-world and making it

inhabitable, which, for social scientists, is part of the is-world to be

investigated. They refuse to admit the reality-descriptive quality of the well-known

Latin proverb, „Quod decet Jovi, non decet bovi!”, which corresponds

closely to the phrase, „All of us are equal, but some more than

others“. They refuse to recognize that phenomenally similar behavior is

not necessarily cognitively similar.

The problem of these criminologists, and perhaps of

the entire activity of criminology, as we shall show in the course of our

study, lies in their attempt to solve the ancient discord between

„is“ and „ought“ by postulating the transformation of the

is-reality into an ought-reality (Gouldner, 1970: 489) as the primary goal of

criminology, without much concern for and perhaps even fear of the presently

existing is-reality.

Though this approach is understandable, since “it is

as extremely painful and threatening for a man to believe that what is powerful

in society is not good, as it would be for the religious believer to feel his

God was evil“ (Gouldner, 1970: 486), we do not consider it to be a viable

approach for engaging in criminology as a science.

We understand science as comprehending and reducing

complexity (Luhmann, 1967: 107), as mapped reality. We regard it as necessary

to distinguish between a pure and applied science in any science and therefore

also in criminology. By criminology as pure science, we mean an activity, which

is restricted to analysis, far away, disconnected from and unrestricted by any

ought-world of change proposals. Based on this perceived is-world encompassing

social ought-worlds, we believe an applied science of criminology is possible.

With this perspective and these assumptions in mind,

we shall now present a central concept of our study, the concept of

marginality.

1.2. The Concept of

Marginality

We propose to understand the is-world of criminal

justice as being governed by what we shall call marginality. By marginality, we

mean (1) the phenomenon that marginal positions exist in all social groupings, (2)

the phenomenon that the marginal positions in all social groupings are limited

in number, and finally, (3) the phenomenon that marginal positions are marginal

relative to the ranking within the particular social grouping. Marginality,

therefore, is characterized by (1) ubiquity, (2) scarcity, and (3) relativity

of marginal positions in social groupings.

Indirectly, we encountered marginality when we

discussed the internal inconsistency of the American Dream. There we noted that

the dream of equality conflicts with the reality of social ranking. The notion

of marginality is nothing but a consequence of structured social inequality in social

groupings.

By introducing our concept of marginality, we

propose to effect „a shift in the problems noticed and investigated and a

change of rules of scientific practice, comparable to the switch in perceptual

gestalten in psychological experiments, when, e. g., the same figure may be

seen as two faces vs. cup, or as duck vs. rabbit“ (von Bertalanffy, 1968:

18). Instead of directing our attention to the inequalities in the social

system, we shall redirect it to its margins. The existence of these marginal positions

is implied by the very fact that we can assume the universality of rank

differentiation in social groupings. The redirection of our attention from the

social ranking to the fact that ranking implies the existence of marginal

positions is especially appropriate if we perceive the Criminal Justice System

as a sub-system of the general social system of structured inequality, which

has the task of deciding whether or not to assign somebody to the social status

of „being a criminal“, i. e., to a marginal status.

By understanding criminal status as a particular

case of marginal status, we take two steps, which have often been postulated.

Firstly, we implicitly recognize that criminal status is a „normal“

social status. Secondly, we free criminology from the „shackles“ of

criminal law definitions (cf., Sellin, 1938: 41).

The normality of criminal status follows from the

assumption of the ubiquity of social differentiation. In contrast, the

assumption of relativity and scarcity of marginal status accounts for the fact

that, for an observer whose standpoint is within a social system, i. e., from

the perspective of his socially constructed ought-world, the marginal status of

being defined criminal appears to be a non-normal social status.

However, our concept of marginality also has the

property of freeing a science of criminology from the shackles of criminal law

definitions. This follows from the assumption that criminal status is only one

type of marginal status and that its allocation procedure can be assumed as

being non-distinct from the allocation of other types of social statuses,

whether they be marginal or not. In our concept, the „criminal“, the

„mentally ill“ individual, the „weird“ person, the

„prominent“ man, Becker’s (1963) „outsider“, as well as the

„leader“, are all defined as marginal persons, but without the

„reality“-restrictive stigma of being good or being evil. Their

position is perceived as the result of a social evaluation process, or more

precisely, of a sequence of social evaluation processes, each not necessarily

consisting of the same evaluators as the previous one, except for the

(changing) self of the evaluee.

Therefore, the proposed concept of marginality is a

way to synthesize several perspectives of the „observed“ socially

constructed realities into a more complexly constructed reality. It takes

Durkheim’s hypothetical „society of saints“ (Durkheim, 1885: 12)

seriously, but goes beyond it; for it claims that corresponding to the

negatively evaluated „deviant“ saints, this society will also have

its “weird”, its “mentally ill”, and its “saintly” saints. It extends Quinney’s

(1970:23) elaboration of Durkheim’s (1885:13) theory of the social reality of

crime to the acquisition of social status, providing us with possible insights

into the process of assignment to a marginal position in a social system, as

well as insights into the process by which the status assignment is confirmed

or altered.

Certainly, however, the mere substitution of the

term “criminal” by the term “marginal” will have the effect of de-metaphysicizing

the study of “crime”.

The theory of the social reality of crime is where

we are today. It is a significant advancement over where we were before, as

this theory can integrate much of the factual information gathered by

generations of criminologists. By having introduced the concept of marginality,

we intend to indicate where we might go from there because the stubborn search

for a science of criminology is not yet over.

1.3. The Model

of “Games for Status”

Corresponding to the nature of concepts – – they are

neither true nor false, but tools designed to capture relevant aspects of

reality and thus “constitute the definitions (or prescriptions) of what is to

be observed” (Merton, 1968: 143) – – our task will be to construct within the

novel reality created by the concept of marginality a theory explaining the

mechanism of status allocation within the multidimensional social evaluation

space.

We shall build two models of status allocation. The

first one is a general model of status change, where the essential factors and

the dynamics of status change are unfurled. The second model, describing the

dynamics of attaining criminal status, is a special case of the general mode.

It is characterized by the fact that criminal status is one type of marginal

status and that its assignment occurs only after an institutionalized ritual,

which is performed by the candidate for criminal status and by various agents

of the Criminal Justice System.

In constructing our models, we shall employ a technique

we often observe in economic literature. There we are used to watching the

growth of a tender theory-seedling through a succession of imaginary worlds.

These are the imaginary worlds of perfect markets, rational behavior, perfect

certainty, two-period worlds, etc. In a sequence of hypothetical tests, where

each one takes place in a world harsher (more “realistic”) than the previous

one, the theory-seedling weathers to a mature theory that can exist and survive

in the complex “real” world. Adopting this technique seems to avoid a significant

problem often confronting behavioral sciences: The Sacrifice of the “Gestalt”,

the complexity, on the altar of reductionism for the sake of exposition.

After the final construct is non-contradictory to

empirical findings and has also been shown to order these findings into a

general system, we shall consider this construct a mapping of reality, reduced

in complexity. On this map, we shall be able to recognize previously

disregarded or unknown interrelations within social systems, and we shall be

able to clarify the relationship between the is-world and the ought-world of

criminal justice.

Our first model deals with status change and status

maintenance in social groupings. It attempts to penetrate the dynamics

effecting a change of the social status X at time t0 to the new

social status Y at time t1 where X and Y can be either the same

status position, or where X ranks higher or lower than Y, and where X and Y are

status positions within the same social grouping. By grouping, we mean any

social entity consisting of at least two persons. Therefore, a grouping could

be a dyad as well as a social system with the high complexity of the

interrelation between its members.

Defining social status as perceived esteem (cf.,

Homans, 1961: 149), we understand the members of social groupings as being

constantly engaged in social exchange activities. Their exchange object is

esteem in various „esteem-currencies“. Exchange theory, as it was

developed for the social sciences by Thibaut and Kelley (1959), Homans (1961),

and Blau (1964), describes and explains this process. It seems, however, that

we can further clarify the notion of social exchange if we take a look over the

fence and observe how another area of science, namely economics, handles the

problem of exchange.

Economists have tried to deal with the problem of

exchange in various ways, one of them being decision and game theory. For our status

change and status maintenance model, we intend to borrow from economics the

descriptive elements in the theory of bargaining games and a modern version of

the rationality postulate. Correspondingly, we choose as the label for our

basic model: „Games for Social Status“.

As a unit of social organization to be analyzed, we

select the encounter, which we define as a sequence of interactions consisting

of at least one action and one response. Unfolding the status change and status

maintenance model, our attention is directed towards the factors that influence

the allotment of esteem by and among the parties of an encounter. We shall

develop the idea that life chances do not depend primarily on social conduct;

instead, as we shall show, the dominant factor for the allotment of esteem in

an encounter is the status quo ante of the participating „players of the

status game“. We shall also show that phenomenally similar behavior is not

necessarily conceptually similar; instead, it is the social status, i. e., the

perceived esteem, which confers the conceptual quality to a behavior. Finally,

our model will confirm the factual information about status movement, namely

that any social status is typically a viscous, „sticky“ state, which

is more likely to be enhanced rather than changed by an encounter.

Our second model is an extension of the basic model

to the process of criminalization. We shall call it „Games for Criminal

Status“. Through this model, we shall solve the contradiction, which seems

to exist between the statements that social status usually is a

„sticky“ state and our assumption that the criminal status is a

marginal status, which typically does not correspond to the status quo ante of

the first encounter with an agent of the Criminal Justice System.

We shall solve the seeming contradiction by

understanding the criminalization process as a sequence of encounters conceived

as bargaining games and by distinguishing four steps in the process of the

allotment of criminal status, i. e., in the process of becoming a person who

has been adjudicated as having committed a „crime“.

The „offender“ is processed, as a rule,

sequentially in four encounters with an agent of the Criminal Justice System.

These encounters, ending with the assignment of criminal status, occur between

the actor and the general public and the „victim“, the police, the

prosecutor, and the court. Each encounter, compared with everyday encounters,

is highly ritualized. Only one party in the encounter, the agent of the

Criminal Justice System, has both the freedom and, sometimes, the duty to

choose partners. This is because he has, on the one hand, more partners and

games available than his time would permit, and on the other hand, he has to

choose at least a few partners and play a few games if he is an agent of type

2, 3 or 4.

We propose, therefore, to understand the four steps

towards criminalization as a recruiting process by which it is sequentially

determined who is eligible for criminal status and who is not. Hence, the

criminalization process can be analyzed as a sequence of encounters, of

bargaining games for criminal status, systematically connected as status

degradation ceremonies. The label „criminal“ is awarded after a

succession of encounters, starting with encountering the victim and ending with

encountering the court. At any given time, the subsequent encounter takes

place, if and only if the previous encounter permits the entrance into the subsequent

encounter, that is if in the previous encounter a behavior has been defined as

criminal behavior and the status of the actor has been downgraded, e. g., to

the new status of „being a suspect“, „being an accused“, or

„being a defendant“.

The details and the results of the model agree with

the factual information about the criminalization process because the model

predicts an inverse relationship between social status quo ante and the chance

to attain criminal status. As our model is non-contradictory to the empirical

findings, we can accept it as an adequate mapping of the process by which

criminal justice is distributed. According to the model, the social reality of

criminal justice is part of a general structured social inequality. Contrary to

the ought-world of criminal justice, it perceives the chance to attain criminal

status as differentially distributed in social groupings.

Our model presents us with an uncomfortable reality

because this reality conflicts with the ought-world of criminal justice. Within

our perceived is-world, conduct, which can be defined as a crime, according to

the relevant (criminal) code, is only a necessary but not a sufficient

condition for attaining criminal status. Just as in our analysis of everyday

status change and status maintenance, the status, which exists before the first

encounter, is the dominant factor for any new status. The role of the

phenomenal conduct is secondary, as its conception depends on the perceived

status quo ante.

Through our model, we try to dissociate ourselves

from the traditional approach to criminology. In contrast to this approach, we

regard criminal status as one type of marginal status, thereby implying that

criminal status positions are ubiquitous, scarce, and relative in any social

grouping. We also imply that criminal status is attained in processes similar

to the ones by which social status in general is acquired. We understand the

model as a concretization of the labeling approach, which focuses on the

offender dealing with the Criminal Justice System.

However, with our model, we also try to present a

„radical“ alternative to the „radical“ neo-romanticism in

American social science as represented, for example, by Alvin W: Gouldner

(1970). We see Gouldner’s approach as reactive and inconsistent with its

objectives.

We have in common with this approach the discomfort

with a system of structured social inequality, administered and maintained in

part by the Criminal Justice System. We share the attitude that the idea of

„justice“, reified in the Criminal Justice System, is a functional

device for maintaining structured social inequality, a device that obscures the

selection of marginal persons from relatively powerless status groups.

However, the radical-reactive approach expresses its

discomfort by constructing an ought world. Its favorite subject is the

political and economic suppression of the weak by the powerful. Structured

social in-equality is seen as a characteristic of particular social systems,

not of social systems in general. The reactive component of the approach

invalidates the radical one because the rules and the setting of structured

social inequality are implicitly acknowledged. Contrary to its own explicit

intentions, the radical-reactive approach is implicitly as system-conservative

as the traditional approach to criminology.

In contrast to the radical-reactive approach, we

attempt to communicate our discomfort through an analysis. Our model of the

criminalization process shows that there is an is-world of criminal justice

where justice is bargained, protected by an ought-world, where justice is

equally distributed. Through our analysis, we attempt to penetrate the

protective screen of the ought-world, which, if successful, has repercussions

on the is-world. We try to conceptualize social differentiation and, therefore,

social marginality in general, whether in the social system of American society

today, in a social system of a tribe of headhunters, in a small group, or a

society of saints.

The proposed analysis of the Criminal Justice System

as „Games for Criminal Status“, then, could be relevant through its

implications for our perception and administration of „justice“.

These very implications bear the possible necessity of a reorientation of

criminology from a caretaker of rationalizations toward a critical science.

In the past, when presenting the ideas of the

concept of marginality and games for criminal status as a possible approach to

map the reality of the „familiar chaos: our ordinary everyday social

behavior“ (Homans, 1961: 1), traditional criminologists have misunderstood

the proposed approach as „value-laden“. From the radical-reactive

side of the fence, the response is even more perplexing at first: What is your

idea good for? What are the implications for social policy? The criticism was

stunning until realizing that the disagreement went deeper than content and

form. It concerns a disagreement in what social science is about.

Our first task, and our next chapter, will therefore

clarify the position from which the basic concept and the models giving it

substance were developed. This will be necessary to delimit the position taken

from the traditional and the now fashionable radical-reactive approach.

2. BEYOND THE „COMMON

SENSE“: TOWARDS A SCIENCE OF SOCIAL DIFFERENTIATION

The „Concept of Marginality“ and the model

of „Games for Criminal Status“, as we shall develop them in the

course of this study, are an adequately reduced reality, if understood from a

position of value-neutrality in social science. By value-neutrality in social

science, we mean an approach which neither proclaims to be free of any values,

as traditional criminology is an accused of doing, nor consciously infuses

values into social science research, as the radical-reactive approach professes

to do, but instead tries to avoid values.

In this chapter, we shall show that the endeavor to

do criminology as a science necessitates stepping beyond common sense. This, in

turn, implies value-neutrality, a pure science approach, and a redefinition of

criminology as a science of social differentiation. By stepping beyond common sense,

we mean stepping beyond „What Anyone Like Us Necessarily Knows“

(Garfinkel, 1967: 54), or in other words, perceiving as social

reality-to-be-analyzed the is-world (phenomenal world) and the everyday

ought-world (conceptual world). Criminology understood as a science, i. e., as

an activity trying to comprehend and reduce complexity, has to take this step

because „constructs of the social sciences are, so to speak, constructs of

the second degree, that is, constructs of constructs made by the actor on the

social scene, whose behavior the social scientist has to observe and to explain

in accordance with the procedural rule of his science“ (Schutz, 1953: 59).

We shall begin our discussion by demonstrating that

the controversy over the „warmed-over stock issues: the difficulty of

defining what is crime and who is the criminal“ (Blumberg, 1967: ix)

characterizes traditional criminology as a caretaker of rationalizations. We

shall argue that „criminology“ is a misnomer, or at least,

inadequately and misleadingly describes the activity of a social science

dealing with crime, the criminal and criminal justice in society. Then, to

delimit our approach from the currently fashionable radical-reactive approach,

we shall discuss the necessity of value-neutrality and a 1’art pour 1’art

attitude in social science. There we shall explain our notion that social

science is a social activity, i. e., that a metascience of social science again

is social science, and we shall demonstrate value-neutrality as an attempt to

avoid everyday ought-worlds. Furthermore, in the third section of this chapter,

we shall revisit our concept of marginality. We shall point out the normality

of „crime“ and „criminals“, and we shall argue based on the

earlier discussion in this chapter that social science „criminology“

has to be redefined as a science of social differentiation. Only after the

problem of common sense in social science and specifically in criminology is

extensively presented do we believe our model of „Games for Criminal

Status“ as a mapping of criminal justice can be made intercommunicable.

2.1. Criminology as

Caretaker of Rationalizations

Turning our attention to the traditional approach in

criminology, we perceive its present state still adequately described by

Sutherland (1947):

Much factual information regarding crime has been

accumulated over several generations. In spite of this, criminology lacks full

scientific standing. The defects of criminology consist principally of the

failure to integrate this factual information into consistent and valid general

propositions.

Sutherland made this statement in the preface to the

fourth (1947) edition of Criminology.

One generation or 23 years later, in the eighth edition of the same work by

Cressey, we read: „Criminology is not a science, but criminologists hope

it will become a science“ (Sutherland and Cressey, 1970: 20).

These are sardonic, however, acceptable summaries of

the work of the elders in criminology made by two of its most highly respected

members. We contend that the principal reason for the failure of criminology as

a science is the commonly shared research bias, which prescribes the delimitation

of criminology by examining „crime“ and „criminal“, however

widely defined. We shall demonstrate that the battle over definitions is a

battle of irrelevancies, fought on the battleground of first degree constructs,

i. e., „constructs made by the actors on the social scene“ (Schutz,

1953: 59). The controversy over definitions shows that traditional criminology

parallels the everyday conceptual reality rather than supersedes. This

controversy characterizes traditional criminology as a caretaker of common-sense

notions.

2.1.1. The Controversy on

Definitions of „Crime“ and „Criminal“

There is not much agreement among the contestants in

the controversy except on two points:

a) A delimitation of the field of criminology is

necessary and feasible. What has to be „found“ is a definition of

„crime“ and „criminal“.

b) Given a definition of „crime“, this

automatically defines as „criminal“ individuals who

„commit“ these „crimes“; and, given a definition of

„criminal“, this automatically defines as „crimes“ the acts

committed, if they are connected with the evaluation of an individual as

„criminal“.

Before showing why we disagree even on these points

with the traditional approach to criminology, we shall briefly consider the

aspects of this controversy as they are presented by four of the chief

participants: Thorsten Sellin (1938), Edwin Sutherland (1945), Paul Tappan

(1947), and Richard Quinney (1970).

Like many searchers in criminology, Thorsten Sellin

(1938) expected to arrive at generalizations, which state that if a person of

type A is placed in a life situation of type B, he will violate the norm

governing that life situation. Postulating that general propositions of

universal validity are the essence of science, Sellin asserted that the

variability in the legal definitions does not permit the formulation of the

universal categories required in all scientific research. He, therefore,

proposed the study of conduct norms in general by isolation and classification

of norms into universal categories rather than only the study of crimes as

defined by the criminal law. For social science criminology, then,

„crime“ is the violation of conduct norms.

Like Sellin, Sutherland (1945) was dissatisfied with

the use of the legal definition of „crime“ in social science research

because it arbitrarily excludes behavior, which is similar to behavior

classified as „crime“ according to the legal definition. Sutherland’s

approach to the problem of the definition of „crime“ and

„criminal“ was to include within the scope of theories of criminal

behavior all behavior that is legally sanctioned and socially injurious. The

legal sanctions he had in mind were not restricted to criminal law but included

those in civil law.

Paul Tappan (1947) found the proposed sociological

definitions of „crime“ and „criminal“ perturbing. He

interpreted them as arising from the „desire to discover and study wrongs

which are absolute and eternal rather than mere violations of a statutory and

case law system which vary in time and place; this is essentially the old

metaphysical search for the law of nature“ (Tappan, 1947: 41). He

criticized Sellin‘ s and Sutherland’s universal concepts for the absence of

criteria defining such terms as „injurious“. Tappan contended that

crime, as legally defined, is a sociologically significant province of study,

whereas the „white collar criminal“, the violator of conduct norms,

and the antisocial personality are not criminal in any sense meaningful to the

social scientist unless they have violated a criminal statute.

Richard Quinney (1970) has provided us with one of

the most recent definitions of „crime“. He defines „crime“

as „a definition of human conduct that is created by authorized agents in

a politically organized society“ (Quinney, 1970: 15). „The social

reality of crime is constructed by the formulation and application of criminal

definition, the development of behavior patterns related to criminal

definitions, and the construction of criminal conceptions“ (Quinney, 1970:

23). Quinney uses the term „crime“ in a somewhat unusual sense.

Sellin, Sutherland, and Tappan employ the term abstractly when they discuss the

rules according to which the social reality is constructed. Quinney, however,

talks about the process concretely when he implies that the rules about how

social reality should be constructed might not necessarily correspond to how it

is actually constructed. Equivalent to Quinney’s definition of „crime” is

that crime results from an evaluation of human conduct. Instead of attributing

the result of concrete evaluation processes to the person adjudicated, the

„criminal“, Quinney attributes it to a conduct, the

„crime“.

2.1.2. Criminology

— A Misnomer?

Common to all four participants in the controversy

is a basic assumption of traditional criminology. This assumption presupposes a

fundamental difference between „crime“ and „criminal“ on

the one hand and behavior and status not evaluated as „crime“ and

„criminal“ on the other hand. The difference from everyday life is

perceived to be so drastic that a separate social science is justified. A

powerful ally for the assumption seems to be the „common sense“, the

„What Anyone Like Us Necessarily Knows“ – grasp (Garfinkel, 1967: 54)

of everyday life.

However, this powerful ally does not appear to be

mighty at all from a phenomenological perspective. On the contrary, from this

perspective, it seems that traditional criminology, because of this alliance,

falls victim to one of the cruelest laws of science, which says that the scope

of the research question determines the range of the possible research results.

The history of sciences is full of examples where paradigms proved to be

inadequately reality-descriptive because of their reality-restrictive a-priori

assumptions (see, e.g., Conant, 1947; Kuhn, 1962).

Today’s most avid victims appear to be the social

scientists, especially the religious believers in empiricism, the centipede leg

counters, as their critics sometimes call them. They and the other social

scientists must face the problem that, while they spend their lives within the

conceptual everyday reality, i. e., within constructions of the reality of the

first degree, in their work, they must build second-degree constructs of the

social reality. Traditional criminology, it seems, has run aground because of

this problem.

The controversy on definitions shows that the

traditional approach to criminology takes the etymology of the term

„criminology“ rather literally. Etymologically,

„criminology“ means the scientific study of „crime“ and

„criminals“. The term was introduced one century ago by Rafaele

Garofalo (1885), who used it as the title of his book. It was at that time an

appropriate description of the activity of criminologists.

Today, six academic generations later, we have to

ask ourselves whether the term „criminology“, which might have been

appropriate at one time, is a misnomer and a mistake because of its implicit

a-priori assumptions.

It is no longer self-evident that there can be a

separate area of science, restricting itself to a behavior and its evaluation,

whether it is called „crime“ and „criminal“ or otherwise.

On the contrary, it seems a more reasonable approach to ask a preliminary

question. Before discussing which definition of „crime“ and

„criminal“ provides an adequate delimitation of criminology, we must

ask whether a social science of a behavior is possible at all.

Quinney’s work, and before him the labeling

approach, did cast the first shadow of doubt on the appropriateness of the name

of the science. Though Quinney does not seem to relinquish the tacit assumption

of traditional criminology, he takes the first step towards it by postulating

that what used to be perceived as a phenomenal reality, namely

„crime“ and „criminal“, are both a conceptual and a phenomenal

reality.

The consequence of this view is that to understand

the person and the act, we have to trace the process which led to the

evaluation. Our attention has to be redirected from the result of the

evaluation process to the evaluation itself. However, suppose we are willing to

take this step. In that case, there is no reason to accept, as Quinney still

does, an a-priori assumption of a fundamental difference between

„criminal“ and everyday social evaluation processes, such as to

justify the maintenance of a separate science dealing exclusively with

„crime“ and „criminal“. Instead, we must either relinquish

criminology as it is presently understood to another social science, or we must

imbue it with new meaning.

Therefore, Quinney, one of the youngest elders in

criminology, legitimates with his compilatory theory of social reality the

revolt against the oldest and most tenaciously held dogma of criminology.

He himself seems to be only dimly aware that his

work facilitates the death blow to the traditional approach to criminology. In

his book The Problem of Crime, he

states somewhat astounded, somewhat proud: „I have found, to my own

satisfaction at least, that an attention to crime can illuminate many of our

problems. Crime has something to do with the most profound of all sociological

problems – the relationship of the individual to his society“ (Quinney,

1970a: vi).

Given our perspective, however, we can no longer say,

„crime has something to do with

the most profound of all sociological problems“. Instead, we have to say

that „crime“ i s one of the possible relationships of an individual

to his society. The controversy on the definitions of „crime“ and

„criminal“ to delimit the subject matter of criminological

investigation, then, is not only controversy on irrelevancies, but also a controversy,

which is misleading by its problem formulation. Like the medieval scientific

controversy within alchemy, it has and will continue to make us lose sight of

some basic assumptions on which the arguments are founded.

2.2. Value Neutrality in

Social Science

In the discussion up to now, we have attempted to

point out how questionable it is to perceive „criminology“ as the

scientific study of „crime“ and „criminals“. We used some

recognized elders, Quinney, Sutherland, and Cressey, as our star witnesses in

our case against the defendant „traditional criminology“.

Nevertheless, we assumed the existence of a scientific activity

„criminology,“ which we, in contrast to the traditional approach, no

longer perceive as a separate social science studying „crime“ and

„criminal“, but understand as a part

of social science. In this new concept, „crime“ is seen as a socially

constructed reality, which can be studied, only as one of the possible

relationships of an individual to his society.

Given this conception of criminology, we have to

take issue with the currently fashionable radical-reactive approach in social

science. We shall contrast our position, which can be described as a position

of value neutrality, from the position of the radical-reactive approach.

We shall accuse the radical-reactive approach of

confusing social science problems with social problems, thereby confusing

constructions of reality of the first and the second degree. Furthermore, we

shall try to show that the social policy implications of a particular research

project are inadmissible in social science. Arguing that an „applied“

science necessitates a „pure“ science, we shall demonstrate that

value-neutrality and a l’art pour l’art approach are indispensable in social

science and, therefore, in criminology.

We shall begin our discussion by illustrating the problems

which an „l‘ art pour l‘ art“ approach to social science presently is

encountering. This will be done by choosing Gouldner (1970) as representative

for a value-oriented social science, which deems itself as radical but is

understood by us as radical-reactive. We shall discuss Gouldner’s objections to

a value-neutral position and point out that to remove the inconsistencies in

his work, even his so-called radical stance would entail an initially value-neutral

approach to social science.

Expanding on this idea, we shall try to clarify in a

second subsection what we see as the problem of common sense in social science,

i. e., the problem that social science itself is a social activity. In the

third subsection, we shall postulate that a value-neutral approach to social

science is a way to avoid many of the ought-worlds, which presently entangle

social science with ought-worlds of the first degree, i. e., with common-sense

notions about the phenomenal world.

Only after this extended discussion of values in

social science can we go about filling the empty hull of the term

„criminology“ with meaning.

2.2.1. Gouldner’s Complaint

and the „l‘ Art pour l‘ Art“ Approach to Social Science

Alvin W. Gouldner has a problem: „It is as

extremely painful and threatening for a man to believe that what is powerful in

society is not good, as it would be for the religious believer to feel his God

was evil“ (Gouldner, 1970: 486). Gouldner attempts to solve his problem by

proposing a „radical“ sociology whose „historical mission . . .

is to transcend sociology as it now exists“ (Ibid: 489), and which helps

„to produce a new breed of sociologists“ (Ibid: 490), the MANLY ONES, who see the „traditional theories . . .

as timidity generating creations of timid men“ (Ibid.: 8).

Gouldner experiences and expresses in his poetic

aesthetic way the ancient discord between „is“ and „ought“,

i. e., in Gouldner’s terms, the tensions between permitted and unpermitted

worlds. Gouldner shares this problem with many latter-day social scientists

whose patron saint he became as the author of „the coming crisis of

western sociology“.

The large number of social scientists who share

these beliefs, coupled with their zealous intolerance against non-believers

(which they justify by the usurpation of the epithet „radical“),

forces the excavation of the long-buried discussion on values in social

science. As a result of this discussion, we hope to demonstrate the position

from which the concept of marginality and the model of „Games for Criminal

Status“ were developed.

We clarify our position with the very arguments

Gouldner uses to establish his „radical“ sociology.

A crucial issue in the discussion of values and

social science seems to be: Social science — what for? This question underlies

Gouldner’s complaint, or, rather, the sensation of impotence to

„discover“ a satisfactory answer to the question i s Gouldner’s

complaint as well as the „coming crisis of western sociology“.

Social scientists, who regard themselves as radical

and are recognized as such by other social scientists who also perceive

themselves as radical, have made the question of the purpose of social science to

their existential core problem. They seem to expect an answer of astral quality

and, being unable to discover the answer, discover instead the decline of the

sociological occident.

We shall propose an answer of more telluric than

astral quality. We shall contemplate the idea that social science is

„merely“ a form of consciousness, assuming „that human events

have different levels of meanings, some of which are hidden from the

consciousness of everyday life“ (Berger, 1963: 29). The purpose of social

science, then, is the satisfaction of a playful curiosity on the part of the

social scientist (Weber, 1918: 137).

According to some people’s standards of manliness,

such an approach certainly has to appear unmanly. Manly, according to their

standards, is to change the world „for the better“. To avoid part of

their harsh criticism and make the approach at least initially more palatable,

let us rename our approach from „playful curiosity approach“ to

„l‘ art pour l‘ art approach“.

Our endeavor then is to show that even the

„manly“ intention of changing this world for the better necessitates an

„l‘ art pour l‘ art approach“ to social science. From the standpoint

of either approach, we contend that it is well worthwhile to insist on a

division between pure and applied social science, even if the demarcation line

is difficult to draw and, as Gouldner’s complaint exemplifies, is also painful

to draw.

Looking backward to Gouldner’s complaint, then, we

shall have seen and will continue to see that jolting collective reality are a

painful activity and that bewailing this fact does not live up to Gouldner’s

own „radical“ standard of manliness in social theorizing — that

Gouldner‘ s complaint is the „timidity-generating creation of a timid man“

(Gouldner, 1970: 8).

2.2.2. The Problem of

Common Sense: Social Science as a Social Activity

Gouldner suggests „that a significant part of

social theorizing is a symbolic effort to overcome social worlds that have

become unpermitted and to readjust the flawed relationship between goodness and

potency, restoring them to their ’normal‘ equilibrium condition, and/or to

defend permitted worlds from a threatened disequilibrium between goodness and

potency“ (Gouldner, 1970: 486). He scorns the traditional sociological

theories as wrong or irrelevant, and postulates a „radical“ social science,

which recognizes the existence of the fact that a social scientist exists in a

field of social gravitation and works toward a solution of the dilemma of

circularity of social theorizing.

As a first step to refute Gouldner’s argumentation,

let us discuss the implications of the notion that social science is a social

activity. Based on the idea that our social life, as social scientists and as

human beings, happens in a socially constructed reality, where the personal

reality of the „normal“ individual is embedded in some collective

reality, and where collective realities of different generality are congruous

with each other, we shall investigate the interaction between some of these

realities and the theorizing of social scientists.

Let us start with a very general collective reality,

the Z e i t g e i s t, and observe how Gouldner’s „radicalism“ is the

consequential development of the interaction between the Zeitgeist and social science in the United States.

We call this type of interaction the gross cycle of social science and contrast

it to other, smaller cycles in which the social scientist finds himself, e.g.,

in the interaction of his theorizing to that of his colleagues in the community

of recognized scientific practitioners.

2.2.2.1. The Gross Cycle of

Social Science

American social science is characterized by

unparalleled provincialism. Reading any book on social science generates the

impression that social science is non-existent outside the American Empire. The

provinciality of American social science makes the task of describing its

development up to the present day neo-romanticism relatively easy.

We can distinguish roughly three stages in the

development of American social science: The Chicago School, the time of

empiricism and grand theory, and the latter-day romanticism. Each of the three

stages reflects the political and economic consciousness of its time and

reflects the gross cycle American social science is subjected to.

The once dominant Chicago

School is perhaps the first

faint-hearted budding of social science in America, worth mentioning for our

purposes. As an heir to the muckraking tradition, this school replaced

newspaper exposes with monographs. It was a school of „social

issues“, of „social problems“, with an outlook of the

„reform-minded Midwest and its dislike

for the industrial and financial centers, with their capitalist exploitation,

boss rule, and religious ’superstitions‘ “ (Roth, 1971: 47). It had its

apex between the two world wars, when the underdog, the poor, the derelicts,

the hoboes, the prostitutes, and other socially weak persons were the overdogs

of social science.

The second significant development of American

social science replacing the Midwestern isolationism of the Chicago School

started with recognizing the possibility of employing social science for policy

decisions. It was the period of grand theory and empiricism. An immense amount

of funds started pouring in for those demanding money as social science became

a respectable activity. It was the time of empire-building, both by the

empirical-minded social science and the Parson-type grand theory, which today

is the favorite object of latter-day sociologists‘ scorn.

In this time, the empirical method developed into empiricism

of sometimes grotesque extent. A description of the typical activities of this

period, self-reported and without self-consciousness, is Hammond’s (1967) collection of Sociologists at Work: Essays on the Craft of Social Research. In Hammond’s anthology, we

can observe how some of the most illustrious names in social science make fools

out of themselves. The perversity of the situation is emphasized because even

the most sardonic critic of empiricism could not have written a better satire

on the movement than the immediate participants.

Since the beginning of the sixties, we can observe a

decline of empiricism as government support for social research decreased. The

much-abused grand theory remained, changing its content but not its form.

Mills‘ T he Sociological Imagination (1959)

is the classic example. The decline of empiricism and the rise of

„radicalism“ in social science came when the fiasco of the American

foreign policy with its ill-concealed neo-imperialism could no longer be

masqueraded behind a helping-brother image. Inside and outside the United

States, it became apparent to the on-lookers that the United States

was an ill-tempered Big Brother in its tantrums. As a consequence,

„radical“ sociology is introverted sociology.

„The severe domestic crisis in the United

States since the mid-sixties in general, and fiascoes such as the abortive

Project Camelot in particular, have resulted in a refocusing on domestic issues

and a retrenchment of foreign area studies“ (Roth, 1971: 48). The

attention of social science is concentrated on domestic social problems and the

political struggles within the ghettos and the universities. “It revolves

around the poles of legitimacy and usurpation, analyzing the perennial triangular

struggle among rulers, staff, and subjects throughout history“ (Roth,

1971: 48).

The tottering of the colossus had its repercussions

on its parasites. The once so almighty empiricist social science and the

traditional grand theory today are subjected to an increasingly harsher

critique. Its critics are the self-professed radicals. The new social science

is of an introverted, brooding kind. The young ones dislike the world their

elders have left them. In a typical generational conflict, the elders are

attacked for their principles, which are perceived to have led to the inherited

quagmire. The reason for the elders‘ failure is sought in their

„irresponsible“ attitude towards values.

The elders profess to be value-free—their offspring

revolt against this. We, therefore, can understand the present reaction against

value-free social science as the reaction of disappointed former believers and

their sons under the guise of the epithet „radical“.

Gouldner has made himself into the spokesperson of

the latter-day sociologists and has won their recognition by acclamation.

However, in the acclamation lies the irony of Gouldner’s situation. When

Gouldner propagates a „reflexive sociology“ and proclaims it as being

radical, the very success of his ideas is a counter-indication of the claimed

extremeness of thought. Instead, as the wide acceptance of his ideas shows,

Gouldner attempts to keep pace with the rapid and sweeping changes in the Z e i

t g e i s t, instead of setting the pace.

Unlike C. Wright Mills, he merely joins the chorus, chanting about the

„emperor without clothes“ — the traditional social science. This

makes him no different from the gullible emperor. He, too, is a follower,

someone who, in his quest for understanding, moves through the world of men with respect for the usual lines of

demarcation. Gouldner’s case, summarized in his own words by what we called Gouldner’s

complaint, exemplifies the case of the social scientist today just as well as

yesterday. A social scientist is inevitably caught in the gross cycle of social

science. Even if he perceives himself as a pacesetter, he is likely to be such

a person because „that’s where it’s at, man“. He is likely to be

„radical“ if it is permissible to be so, or as it appears nowadays

because it seems indecent not to give this appearance.

Like his brother, the „man on the street“,

the social scientist is restricted in the realities he constructs by the

collective reality in which he lives. The „radicalism“ of Gouldner’s

type is a permitted reality embedded in the very general reality, which we call

Zeitgeist. The very fact of its wide

acceptance shows this interrelation.

Gouldner, who thinks that in his quest for

understanding he moves „through the world of man without respect for the usual lines of demarcation“ (Berger,

1963: 18), actually cringes in front of the Zeitgeist

which presently demands „radicalism“ from the youthful adept in

social science — and Gouldner has not much choice to act differently because

social science, according to his confession, is a social activity, and as such

takes place within some form of collectively constructed reality.

2.2.2.2. The Petite Cycles

of Social Science

We now turn our attention to the interaction of

social science with collectively constructed realities of lower generality,

which are perhaps less controversial in respect to their existence than the

reality Zeitgeist.

We now discuss the realities of groups of scientists

adhering to and defending a particular school of thought within their

discipline, and also another type of realities of still lower generality, the

personal reality of the individual scientist. We call the interaction of these

two realities with the research of the social scientist the petite cycles of

social science.

As in the previous section, we start with the basic

assumption — which we share with Gouldner — that the imposition of a

conceptual order upon data is a social activity (cf. also, Conant, 1947;

Beveridge, 1957). Social science as a social activity, then, exhibits

characteristics common to other social behavior. The irony of the situation is

that we investigate social behavior and that even a study of the activity of

the social scientist as an object of investigation is no escape from this

circle.

In traditional sociology texts, the problem of the

petite cycles of social science is usually evaded by a chapter on objectivity

in social science or, more elegantly, by a chapter on what is called

„methodology“. C. Wright Mills was one of the first influential

writers in social science to knock this Holy Cow, and we intend to do our

share.

Christian Morgenstern, a German satirist, has

caricatured the circularity of social analysis in his Palmstroem- poem,

„The Impossible Fact“ (Morgenstern, 1963: 34f.). The philistine hero,

Palmstroem, is run over by a car in this poem. Ignoring his death, Palmstroem

conducts an analysis of the situation:

Tightly swathed

in dampened tissues

he explores the legal issues,

and it soon is clear as air:

Cars were not permitted there!

And he comes to

the conclusion:

His mishap was an illusion,

for, he reasons pointedly,

that which must not, can not be.

Like Gouldner in his complaint, Morgenstern’s

philistine experiences the discord between „is“ and

„ought“, between permitted and unpermitted worlds. Like Gouldner,

Palmstroem solves his dilemma in favor of his idiosyncratic normative reality.

Of course, compared with Gouldner, the phantasy-creature Palmstroem is

immensely less sophisticated and openly egotistical; however, he is

refreshingly illustrative: that which must not, cannot be.

Palmstroem illustrates a petite cycle of social science, where Gouldner’s petit

mal prevents him from realizing it.

Let us start with the observation that the

Palmstroem- problem if it were the object of a social scientific investigation,

would be a problem of Palmstroem’s cognitive balance. Were Palmstroem a social

scientist, however, we could surmise that both he and his social scientist colleagues

would study Palmstroem’s problem with „reality“ as a question of

scientific objectivity. What would be the dimension of inquiry if a

psychiatrist or psychoanalyst did it is superfluous to mention. If we disregard

the soul-doctors, we are still left with the paradoxical situation that the

dimensions of inquiry into „reality“ are dissimilar depending on who the

inquisitor is and who the subject is.

The usual argument for maintaining the different

standard is that the activities of the „scholar“ and the „man on

the street“ are fundamentally dissimilar, insofar as the one balances his

cognition in a way, which is intercommunicable, whereas the „man on the

street“ orders his cognition in a non-methodical way.

This argument brings the discussion into the

disputes raging among the philosophers of science. In the context of this

paper, our counter-arguments will necessarily appear scanty and only scrape the

surface of the ontological problem involved. However, so are the other side’s

arguments, generally, if they are proffered in a context other than the philosophy

of science.

As a response to the argument, which attempts to

justify different dimensions of inquiry depending on who is the object of

inquiry, the scholar or the „man on the street“, we distinguish

between the context of discovery and the context of demonstration.

Traditionally, the context of discovery is left to psychological analysis. In

contrast, the logical analysis of thought is concerned with the context of

demonstration, „i. e., with the analysis of ordered series of thought

operations so constructed that they make the results of thought

justifiable“ (Reichenbach, 1947: 2).

However, Hans Reichenbach (1938: 311), who originated

the distinction of two realms of analysis, naming them context of discovery and

context of justification, already provides at the same time a word of warning

not to overindulge in methodology:

When we call logic analysis of

thought, the expression should be interpreted so as to leave no doubt

that it is not actual thought, which we pretend to analyze. It is rather a

substitute for thinking processes, their rational r e c o n s t r u c t i o n,

which constitutes the basis of analysis. Once a result of thinking is obtained,

we can reorder our thoughts in a cogent way, constructing a chain of thoughts

between point of departure and point of arrival; it is this rational

reconstruction of thinking that is controlled by logic, and whose analysis

reveals those rules, which we call logical laws (Reichenbach, 1947: 2).

Methodology and discussions of scientific

objectivity with their ceremonial formalism, therefore, tend to obscure the

fact that social-psychological dynamics are essential not only in the context

of discovery but also in the context of demonstration. The same tendency to

obscure more than elucidate the problems of the context of demonstration can be

ascribed to those philosophers of science, who, in a logico-philosophical jargonese, write

learned tractates to lay bare the simple-mindedness of formalistic methodology.

Before we get entangled in argument and

counter-argument in their language and on their „level“, let us leave

the tract of science, which philosophers claim as theirs, and take the trophy

of our sneaky and short hunting-excursion with us into the relative security of

a social science discussion. Our trophy is the notion that undisputed by the

philosophy of science, cognitive elements play a role in the discovery and the

demonstration of scientific theories in the same way as they do in the everyday

life of the „man on the street“. For empirical research, this is

confirmed by Rosenthal (1966), who shows by extensive examples that different

observers of the same experiment can come up with results widely differing from

each other. Rosenthal’s study was predominantly concerned with the influence of

the experimenter’s expectations on the subject of investigation, i, e., changes

in reality by expectations. However, the notion that cognitive elements are

present in the discovery and the presentation of a theory implies that

perceptions used to justify a theory are themselves firmly formed and guided by

this theory. Perceptions are dependent on the context in which they are made. Parts

of the context are cognitive factors like the set, expectancies, and

hypotheses. This means, among other things, that under the influence of

theories, there is a tendency towards a disposition and a habit to observations,

which favor theory-conforming observation results (Kuhn, 1962).

We show this through a simple example from the

history of science. According to an excellent account by Conant (1947), for

centuries, the principle that „nature abhors a vacuum“ served to

account for various phenomena, such as the action of pumps, the behavior of

liquids in joined vessels, suction, and the like. The strength of everyday

evidence was so overwhelming that the principle was seldom questioned. However,

it was known that one could not draw water to the height of more than 34 feet.

The simplest solution to this problem was to reformulate the principle to read that

„nature abhors a vacuum below 34 feet“. This modified version of the

horror-vacui theory was again satisfactory for the phenomena it dealt with

until it was discovered that „nature abhors a vacuum below 34 feet only

when we deal with water“. As Torricelli has shown, „nature abhors a

vacuum below 30 inches“ when it comes to mercury. Displeased with the

crudity of a principle, which must accommodate numerous exceptions, Torricelli

formulated the notion that the pressure of air acting upon the surface of the

liquid was responsible for the height to which one could draw liquid by the

action of a pump. The 34 feet limit represents the weight of water, which the

air pressure can maintain, and the 30-inch limit represents the weight of

mercury that air pressure can maintain. This was an entirely different and

revolutionary (Kuhn, 1962) concept and its consequences had a drastic impact on

physics.

Let us analyze the development of the concept of air

pressure for its cognitive elements. We see that at each stage of its unfolding

process, the available perceptions of reality were structured to a consistent construct,

which was able to withstand a methodological inquiry — until new facts were

introduced and perceived as such. Not at any point in the concept’s development

can we point out a methodological mistake. However, we can observe how a

cognitively consistent reality is constructed at each step.

The same process is the object of our study when we, as social scientists, observe the

„man on the street“ building his cognitive world out of perceptions

of his physical and psychical environment. The process is used in the

Rohrschachtest, Murray’s Thematical Apperception Test, and IQ-test.

Solving problems in an IQ-test can be regarded as

perhaps the closest model to constructing scientific theories. There we find,

put to the extreme, Reichenbach’s notion that a methodologically correct

construction is a cognitive construct that is rationally reconstructable. The

„man on the street“, i. e., the subject of an IQ-test, therefore, is

not so fundamentally different in the ways he arrives at the construction of

his everyday world from the scientist, as to warrant the examination of his

cognitive world with two different standards: one methodology, and the other a

test of his cognitive world by „someone who knows“. Neither the

scientist nor the „man on the street“ are persons „who

know“, but both are persons who deal with a socially constructed reality.

If the scientist takes it as warranted to perceive

the constructs of the world of the „man on the street“ with

professional suspicion, there is no reason not to regard his own activity in

the same way. He, too, is caught in a petite cycle of science where social

science is a science and simultaneously a meta-science. Therefore, social

science as a meta-science stands side-by-side with methodology in the

examination of the context of demonstration.

However, let us not stop and assume there is merely something,

which we termed the gross and the petite cycle of social science, the latter

standing for the interaction of the cognitive world with the individual

scientist. That would mean oversimplifying our initial model in which we

claimed the existence of many socially constructed worlds related to each

other, similar to the Chinese boxes buried within each other, as collectively

constructed realities of different generality.

The next world we want to discuss stands in close

relationship to the world we outlined as constructed due to the universal

tendency to cognitively balance our perceptions. This is the world of normal

science.

Historians of science like Conant (1947) and Kuhn

(1962) have consistently pointed out that there are beliefs that are held by

the majority of scientists until a „scientific revolution“ replaces

them with new concepts. Some of the concepts appear hilarious today, although

they were not so to our ancestors. As an example, for a long time, people

believed that the universe revolved around the earth. Moreover, it is not so

long ago that it was a scientific dogma to hold that the earth was flat, with

an edge off of which the incautious might fall; or, to take our previous

example, there was a time when the action of a pump was explained by the

„horror vacui“.

Instead of following the historians of science who

attempted to find the regularities governing the change of concepts through a

historical analysis, we shall use their presentation to demonstrate that

science, and of course, social science is a social activity.

The very persistence with which concepts were

defended against a new school of thought, which had a differing concept, is

perhaps the strongest indication that the imposition of conceptual order onto

data is a social activity. As such, it exhibits characteristics common to other

social behavior.

Merely the intercommunication with his professional

colleagues makes even the lone investigator someone who is involved in a group

activity. His research is in some way the product of others’ prior work and the

precursor of subsequent work (Nisbet, 1970: 28). Within the group of scientists,

there is a powerful control mechanism, which guards the fact that the

personally constructed reality of most individual scientists falls within the

collectively permissible reality.

Kuhn’s (1962) definition of normal science implies

the existence of a powerful defense against non-believers. This can easily be

observed in today’s scientific life. There are a vast number of screening

procedures, formal and informal, guarding the threshold of the community of

recognized scientific practitioners of the respective discipline, barring

heretics from the entrance into or continuance of membership in the community.

The procedures and effects of these control mechanisms are similar to the controls,

which hold the „man on the street“ within the framework of a

collective reality, be it a small group reality or a national reality.

The screening functions, yesterday taken care of by the Holy Inquisition, are

today effectively and efficiently taken care of by the universities and

grant-dispensing agencies (Kerr, 1966). The admission procedures range from admission

to graduate study, acceptance of a project for agency funding, acceptance of a

publication, and acceptance as a tenured faculty member (certified scientist).

There are ingenious control and guidance systems, like the grading system

guaranteeing constant surveillance and intellectual bondage in the early stages

of membership in the community; there are introductory courses that make sure

that the new pledge starts along with the „right“ path to wisdom;

there are degree programs; and last but not least there are the bestowals of

degrees of adjustment.

If the budding savant finally identifies with and is accepted by the community

of recognized practitioners of his choice, this usually means that he also

identifies with and accepts the basic concepts (collectively constructed

realities) in this science. At that time, when his „revolutionary“

spirit seems to be broken, he is allowed to help build and mend the

collectively constructed realities, now that he is fully conscious of the

likelihood of disastrous results for his „career“, should he propose

a nonconformist reality.

Therefore, we can only agree with Lemert’s observation:

Novel paradigms most often are created by youthful

scientists, primarily because they are less committed by prior practice to the

traditional rules of normal science, they are freer to conceive new images of

the world, new sets of rules for problem-solving, and to sympathetically

entertain new classes of facts. By the same reasoning, resistance to new

paradigms is strongest among older scientists, who have long-standing practical

commitments to the established ways of perceiving their world of study (Lemert,

1970: 7).

In the regular day-to-day study of social life, the

cognitive world of the social scientist is subjected to a control system whose

presence does not necessarily penetrate the scientist’s consciousness. This

system is built around him, keeping his cognitive world within the boundaries

of some collective reality. As social scientists, they are not different from

the „man on the street“. In the community of scientific

practitioners, everybody is the victim and at the same time the enforcer of the

control system, which guides us through „reality“. The controls

become visible, they enter our consciousness only when the system penalizes a

deviation overstepping the boundaries of the permissible or tolerable.

„The activity in which most scientists

inevitably spend almost all their time“, therefore, is normal science.

Normal science, however, „is predicated on the assumption that the scientific

community knows what the world is like. Much of the success of the enterprise

derives from the community’s willingness to defend that assumption, if

necessary at considerable cost“ (Kuhn, 1962: 5).

2.2.2.3. Value Neutrality

as an Attempt to Avoid Ought-Worlds

Our operating premise was that social science is the

endeavor of conducting a rational activity to construct second-degree realities,

which successively approximate the „real“ reality, intending to

construct a reality capable of integrating at least one more observed fact than

the presently accepted reality. In the previous section, we showed that the

social scientist is inevitably caught in his time and place’s social reality.

We demonstrated that this is the case because there exists an interaction

between the constructed reality of the social scientist, the second-degree

construction, and the conceptual reality of his social environment. The

situation of the social scientist is more difficult when compared with the

situation of his colleague in „hard“ science since he is directly

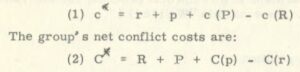

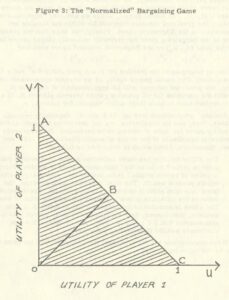

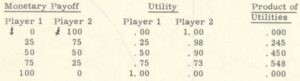

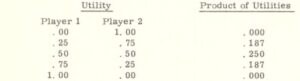

faced not only with the constructed realities of his field but also with the